Dionise Ysabelle Bawal, MD

If there’s one word to describe endocrinologists, it would be festive. After the daily grind of attending to patients and accomplishing whatever tasks are on our to-do list, we like to unwind and get together to dine and dance. We celebrate big wins, such as the induction of new diplomates, and even small victories, such as winning first prize in a dance contest. During conventions, we like to catch up with colleagues, not to forget the singing and dancing that seems innate to most endocrinologists.

For last month’s festivities, we shook things up and became transcultural. Most of you may already be familiar with the Mid-Autumn Festival’s Chinese tradition. It was my first time participating, so let me share some fun facts and my experience as a first-timer. (For our dear Chinese colleagues, please feel free to correct me as this article was based on short interviews and a deep dive into Google, heeheehee).

What is the Mid-Autumn Festival?

The story of the Mid-Autumn Festival goes back more than 3,000 years. It is rooted in the belief that the moon is brightest and roundest during mid-autumn, representing unity and completeness. According to legend, Chang’e, the moon goddess, was responsible for the festival. There was a time when the sky had ten suns. Hou Yi, her husband, would shoot down nine, leaving only one sun to provide light and warmth, thus saving the lives of those on Earth. Because of this heroic act, the queen mother of the West gave him a bottle of elixir that would make him immortal. However, because of his love for Chang’e, he chose not to drink the elixir and asked his wife to keep it for him. Because of his fame, many students wanted him as a master. However, one of his students, Pang Meng, heard about the elixir and tried to steal it. So, one fateful day, while Hou Yi was out with this students, Pang Meng faked an illness and stayed at home. He went to Hou Yi’s house to force Chang’e to give up the elixir. Because she knew that she could not win against Pang Meng, she drank the elixir immediately. The elixir made her fly higher and higher, unable to return to Earth. She stopped soaring when she got to the moon and became immortal. Upon hearing about what happened to Chang’e, Hou Yi was heartbroken. But that night, he found the moon shining very bright with a figure similar to Chang’e. Because of this, he offered fruits and cakes that were favorites of Chang’e to express his love and sorrow. This act became the basis of the tradition of offering fruits and cakes to the moon in mid-autumn.

Legend aside, the tradition was first seen in the Zhou Dynasty in 1045-221 BC, when the ancient Chinese emperors worshipped the harvest moon during autumn. They believed doing so would bring them a bountiful harvest the following year. They prepared sacrifices and offerings to the moon/moon goddess (which I think is Chang’e). At this time, it was yet to be celebrated as a festival.

Fast forward to the Tang Dynasty, these traditions were only practiced by emperors and wealthy merchants as they held celebrations in their courts while appreciating the bright moon. Later on, admiring the moon became a practice among all Chinese families.

It was finally in the Song Dynasty (960-1279) when appreciating the moon was not just a practice but a festival. The 15th day of the 8th lunar month was known as the “Mid-Autumn Festival.” Since then, sacrificing to the moon has become a yearly tradition.

Of Mooncakes

An essential tradition of the Mid-Autumn Festival is the mooncake. I have always been in awe of seeing numerous mooncakes exchanged during this time of year. As I studied these mooncakes closely, it is a round pastry in many flavors and sizes. What’s remarkable is the intricate design of each one; some had Chinese characters on them, others had symbols. In terms of flavors, some are sweet, others are savory, some have red bean paste fillings, and others have nutty flavors.

As Chinese culture is deeply rooted in tradition, these mooncakes are not merely pastries to be given away but also rich in symbolism. The round shape signifies unity and completeness, just like the full moon. Sharing them among family and friends strengthens the idea of togetherness, like how ancient Chinese families spent their nights gazing at the moon together.

Of dice

More than the legends and the symbolism behind this festival, I have also come across an integral part of the festival, at least in the past. Although not very popular anymore, the Mid-Autumn Festival Dice game or “Zhuang yuan bo bing,” is a traditional Chinese game that dates back to the Qing Dynasty in the 1600s. It originates from Xiamen citizens, who believe that mooncakes symbolize good luck, especially for those studying for their exams. Upon learning that, I asked myself, “Now, where were these mooncakes during the board exams?” Kidding aside, they were known as “scholar cakes” and given to those undergoing imperial examinations for junior and senior court administrative positions. The biggest mooncake was given to the top scholar.

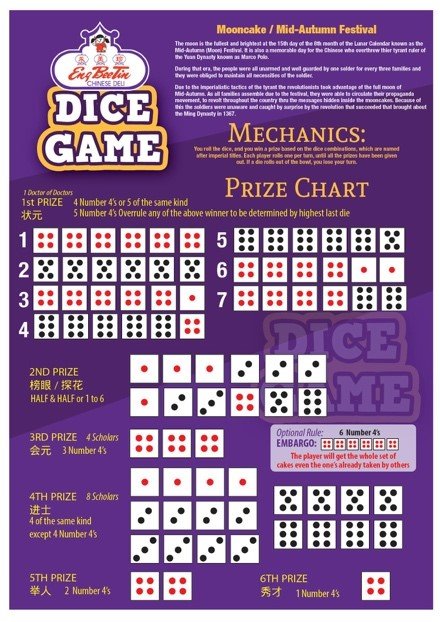

What do you need to play? Six dice, one bowl to toss them in and a set of 63 mooncakes of varying sizes. The largest one, reserved for the grand winner, sometimes measures up to 16 cm in diameter. Each player would have a chance to toss the dice into a bowl, and specific dice patterns entail a prize. I’ve attached a quick kodigo of the winning patterns. I acknowledge Eng Bee Tin for this downloadable summary of winning dice patterns.

I will not go into the details, but basically, the player who gets first prize patterns wins the biggest mooncake. The game has no limit as to the number of players and continues until no mooncakes are left. Each player would carefully toss the dice into the bowl because once the dice rolls outside the bowl, the turn is considered void.

Of Mooncakes, Dice and Endocrinology

Last September 29, some of our training institutions, namely Chinese General Hospital, St. Luke’s Medical Center Quezon City and University of Santo Tomas Hospital, joined the festivities and celebrated the Mid-Autumn Festival. Guided by consultants with Chinese heritage, some of us were lucky enough to experience the celebration for the first time. Again, aside from our love of festivals, endocrinologists are also inherently competitive. You can imagine the excitement and anticipation of each person as we tossed our dice into the bowl, hoping to win the top prize.

Here are some pictures of the Mid-Autumn Festival Dice Game Endo version:

CGH

SLMC QC

USTH

The legend of the mooncake festival embodies love, sacrifice and enduring bond between family members. Just like how ancient Chinese valued these traditions, so do we at PCEDM. Maybe a yearly PCEDM mooncake festival dice game is in the offing? 😉

References:

- “Mooncake gambling odds-on festival favourite”. China Daily. 28 September 2008. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- See, Stanley Baldwin (17 September 2015). “Playing the Mooncake Festival’s centuries-old dice game”. GMA News. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- “Chinese Moon Festival Dice Game” (PDF). Westchester Association of Chinese Americans. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- https://guide.michelin.com/en/article/features/toss-for-tradition-mid-autumn-festival-dice-game

- https://www.chinahighlights.com/festivals/mid-autumn-festival-history-origin.htm

![]()