By Maria Nikki Cruz, MD

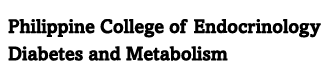

Steatotic Liver Disease (SLD) has various etiologies (Figure 1). Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), Alcohol-associated Liver Disease (ALD), and an overlap of the 2, MASLD and increased alcohol intake (MetALD), comprises the most common causes of SLD.

Figure 1. Steatotic Liver Disease (SLD) subclassification.

The new classification acknowledges that multiple etiologies of steatosis can coexist. The introduction of a separate MetALD subcategory where metabolic and alcohol-associated risk factors coexist sits outside MASLD/NAFLD provides an opportunity to generate new knowledge for this group of patients. Furthermore, the new nomenclature strives to accelerate disease awareness and minimize stigma associated with the use of terms. The prior “nonalcoholic” label is now appropriately named “metabolic dysfunction-associated” emphasizing the metabolic basis for this liver disease, which was long recognised as the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. It allows for a straightforward explanation of the disease as it is easier to understand in the context of its underlying cardiometabolic abnormalities linked to insulin resistance and its association with the patient’s other conditions.

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), previously termed non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is defined as steatotic liver disease (SLD) in the presence of one or more cardiometabolic risk factor(s) and the absence of harmful alcohol intake. The spectrum of MASLD includes steatosis, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH, previously NASH), fibrosis, cirrhosis and MASH-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) is designated in persons with MASLD and steatohepatitis. Within the MetALD group, the contribution of MASLD and ALD will vary according to weekly and daily consumption of alcohol, acknowledging that the impact of varying levels of alcohol intake varies between individuals.

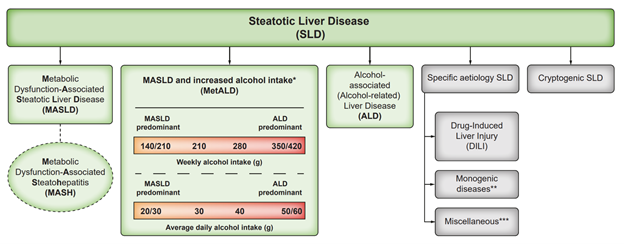

Figure 2. Flow-chart for SLD and its sub-categories

The category MetALD, describes those with MASLD who consume greater amounts of alcohol (20-50 g/day for females and 30-60 g/day for males, respectively), but do not meet the criteria for ALD. ALD is a distinct liver disease (of which steatosis is one of the features) and, thus, is categorised under the SLD umbrella. This should raise awareness of alcohol as a driver of steatosis and highlight the impact of excessive alcohol consumption (i.e., >50–60 g daily in females and males, respectively) irrespective of their association with metabolic dysfunction. One “standard” drink or one alcoholic drink equivalent contains 14 grams of pure alcohol, which is found in the following: (1) 12 ounces of regular beer, (2) 5 ounces of wine and (3) 1.5 ounces of distilled spirits. Therefore, excessive alcohol consumption or heavy drinking is defined as consuming five or more drinks on any day or 15 or more per week for men and four or more on any day or 8 or more drinks per week for women. The simplified diagnostic work-up of a case of SLD is seen in Figure 2.

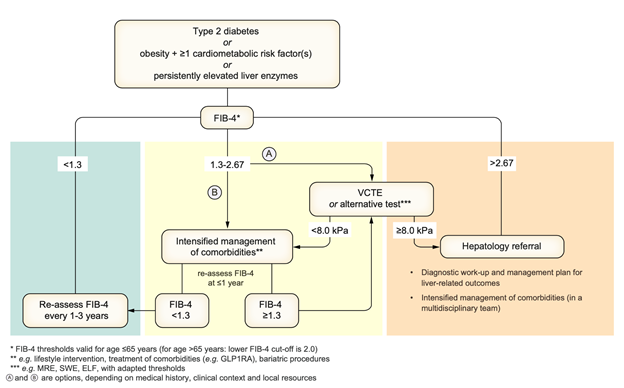

Figure 3. Non-invasive assessment of the risk for advanced fibrosis and liver-related outcomes in individuals with metabolic risk factors or signs of SLD

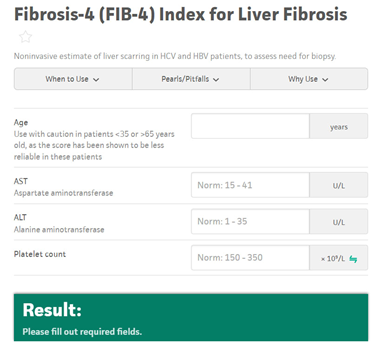

Screening for MASLD with liver fibrosis should be done in individuals with type 2 diabetes, abdominal obesity and >1 additional metabolic risk factor/s) or abnormal liver function tests. A multi-step approach is recommended in adults with MASLD as seen in Figure 3. First, an established non-patented blood-based score, such as FIB-4 (Figure 4), should be used. Thereafter, established imaging techniques, such as liver elastography, are recommended as a second step to further clarify the fibrosis stage if fibrosis is still suspected or in high-risk groups.

Figure 4. Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) Index for Liver Fibrosis

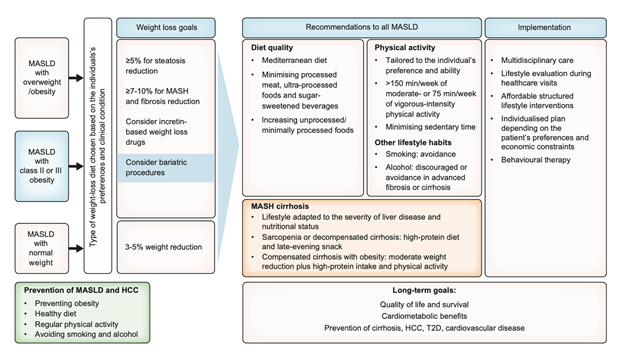

Recommendations for the management of adults with MASLD includes dietary and behavioural therapy-induced weight loss to improve liver injury, as assessed histologically or non-invasively as seen in Figure 5. A sustained reduction of >5% to reduce liver fat, 7-10% to improve liver inflammation, and >10% to improve fibrosis is recommended in adults with MASLD and overweight.

GLP1RAs are safe to use in MASH (including compensated cirrhosis) and should be used for their respective indications, namely type 2 diabetes and obesity, as their use improves cardiometabolic outcomes. However, GLP1RA was not currently recommended as MASH-targeted therapies. Likewise, pioglitazone, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors or metformin are considered safe to use in adults with non-cirrhotic MASH but are also not recommended as a MASH-targeted therapy.

Figure 5. Lifestyle management algorithm for MASLD.

Resmetirom (Rezdiffra) is a new MASH-targeted pharmacotherapy and is the first drug approved by the U.S. FDA for patients with MASH and moderate-to-advanced hepatic fibrosis last March 14, 2024. This drug is an agonist of thyroid hormone receptor-β; agonists of this receptor in the liver promote hepatic fat metabolism and prevent hepatic injury resulting from lipotoxicity.

The MAESTRO-NASH study was the phase 3 trial involving adults with biopsy-confirmed NASH and a fibrosis stage of F1B, F2, or F3. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive once-daily resmetirom at a dose of 80 mg or 100 mg or placebo. The two primary endpoints of the study at week 52 were MASH/NASH resolution with no worsening of fibrosis, and an improvement in fibrosis by at least one stage with no worsening of the MASLD/NAFLD activity score. NASH resolution with no worsening of fibrosis in the 80-mg resmetirom group and 100-mg resmetirom group were achieved in 25.9% and 29.9% of the patients, respectively as compared with 9.7% in the placebo group. Fibrosis improvement by at least one stage with no worsening of the NAFLD activity score in the 80-mg resmetirom group and in the 100-mg resmetirom group were achieved in 24.2% and 25.9% of the patients, respectively, as compared with 14.2% in the placebo group. Diarrhea and nausea were more frequent with resmetirom than with placebo.

MAESTRO-NASH investigators concluded that both the 80-mg dose and the 100-mg dose of resmetirom were superior to placebo with respect to NASH resolution and improvement in liver fibrosis by at least one stage.

These recent updates in the classification of steatotic liver disease paves the way for further research and improvement in the therapeutic options such as Resmetirom in the management of this complex liver disease.

REFERENCES

- EASL–EASD–EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) Tacke, Frank et al. Journal of Hepatology, Volume 81, Issue 3, 492 – 542.

- Harrison SA, Bedossa P, Guy CD, Schattenberg JM, Loomba R, Taub R, Labriola D, Moussa SE, Neff GW, Rinella ME, Anstee QM, Abdelmalek MF, Younossi Z, Baum SJ, Francque S, Charlton MR, Newsome PN, Lanthier N, Schiefke I, Mangia A, Pericàs JM, Patil R, Sanyal AJ, Noureddin M, Bansal MB, Alkhouri N, Castera L, Rudraraju M, Ratziu V; MAESTRO-NASH Investigators. A Phase 3, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Resmetirom in NASH with Liver Fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2024 Feb 8;390(6):497-509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2309000. PMID: 38324483.

- Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, Romero D, Abdelmalek MF, Anstee QM, Arab JP, Arrese M, Bataller R, Beuers U, Boursier J, Bugianesi E, Byrne CD, Castro Narro GE, Chowdhury A, Cortez-Pinto H, Cryer DR, Cusi K, El-Kassas M, Klein S, Eskridge W, Fan J, Gawrieh S, Guy CD, Harrison SA, Kim SU, Koot BG, Korenjak M, Kowdley KV, Lacaille F, Loomba R, Mitchell-Thain R, Morgan TR, Powell EE, Roden M, Romero-Gómez M, Silva M, Singh SP, Sookoian SC, Spearman CW, Tiniakos D, Valenti L, Vos MB, Wong VW, Xanthakos S, Yilmaz Y, Younossi Z, Hobbs A, Villota-Rivas M, Newsome PN; NAFLD Nomenclature consensus group. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2023 Dec 1;78(6):1966-1986. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000520. Epub 2023 Jun 24. PMID: 37363821; PMCID: PMC10653297.

- Chung W, Promrat K, Wands J. Clinical implications, diagnosis, and management of diabetes in patients with chronic liver diseases. World J Hepatol 2020; 12(9): 533-557 [PMID: 33033564 DOI: 10.4254/wjh.v12.i9.533]