Precious Diamond See, MD; Joebeth S. Tabora-Vinluan, MD; Patrick Y. Siy, MD

Case Presentation:

A 39-year-old male presented with a one-week history of persistent, sharp mid-upper back pain following an ordinary yet significant act: lifting a 66 kg object with another person. The pain was non-radiating and rated 9/10 in severity, prompting a clinical consultation.

Question for Reflection:

Can a seemingly minor physical effort in a healthy young adult lead to a vertebral fracture?

Initial Clinical Clues and Diagnostic Work-up

The patient had no history of trauma, falls, or previous fractures, and no neurological symptoms such as numbness, tingling, or gait disturbances. No medications were being taken at the time. Partial pain relief was achieved with Etoricoxib 120 mg, reducing pain to a 5/10; however, bending forward and jumping worsened the pain.

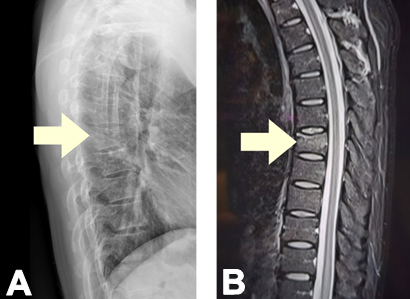

Due to continued symptoms, a thoracic spine X-ray (Figure 1A) was performed, revealing a mild compression deformity at the T7 vertebra. A lumbosacral MRI confirmed the acute compression deformity without spinal cord compression (Figure 2A).

Figure 1. A. Thoracic Spine X-ray showing a mild compression deformity at the T7 vertebra. B. Lumbosacral MRI showing acute compression deformity without spinal cord compression

Clinical Background and Risk Factor Analysis

The patient was generally healthy:

- No comorbidities or history of corticosteroid use.

- No history of osteoporosis or fractures.

- Family history is notable for osteopenia in the mother and metabolic disorders (hypertension and diabetes) on both sides.

- Generaly lives a healthy lifestyle with regular exercise, weightlifting (up to 80 kg pre-pandemic, then 40 kg at home during the pandemic), and no history of smoking or alcohol abuse.

Clinical Question:

What makes a healthy, physically active 39-year-old male susceptible to a vertebral compression fracture?

Physical and Systemic Examination Highlights

- Normal vital signs and BMI (21.7 kg/m²).

- No clinical signs of Cushing’s, acromegaly, hyperthyroidism or hypogonadism.

- No neurologic deficits; however, point tenderness over T7 was appreciated.

- No signs of kyphosis or spinal deformity.

- No blue sclerae, teeth abnormalities. Normal join and skin laxity.

Working Diagnosis and Next Steps

With a low-impact, non-traumatic vertebral fracture, the clinical team suspected underlying osteoporosis. The red flag here: fragility fractures in young individuals are uncommon and merit investigation for secondary causes.

Clinical Question:

What are potential secondary causes of osteoporosis in a young adult male?

Bone Mineral Density and Laboratory Findings

A Bone Mineral Density (BMD) test was ordered, yielding:

- Z-score of –2.1 at the left femoral neck

- Z-score of –2.9 at the spine

- These findings confirmed low bone mass for age.

Further lab tests revealed:

- Low vitamin D (21.6 ng/mL)

- Slightly elevated PTH (79.4 pg/mL)

- Normal testosterone, TSH, FT4, cortisol, calcium, and phosphate

Initial Management Strategy: Anabolic Approach

The patient was started on:

- Calcium + Vitamin D supplements

- Teriparatide 20 µg SC daily — an anabolic agent stimulating osteoblast activity.

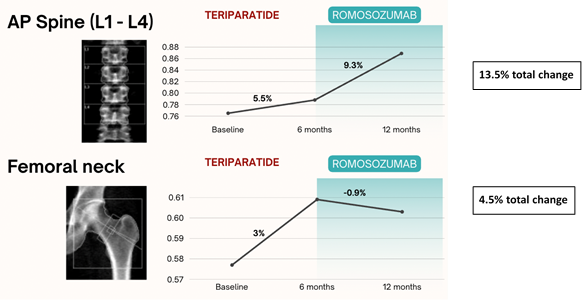

After 6 months:

- BMD increased by 3% at the spine and 5% at the femoral neck

- Osteocalcin slightly elevated, BAP low-normal

Table 1. Comparison of Z-score at baseline, after 6 months and after 12 months on anabolic therapy

Therapeutic Switch: A Targeted Strategy with Romosozumab

At month 9 of teriparatide therapy, bone turnover markers suggested a modest anabolic response, possibly blunted or delayed. In addition, patient has low cardiovascular risk profile, and the patient’s preference for fewer injections, a switch was made to romosozumab 210 mg monthly — a sclerostin inhibitor with dual action:

- Stimulates bone formation via Wnt/β-catenin signaling

- Suppresses bone resorption via OPG-mediated inhibition of osteoclastogenesis

Clinical Question:

Given the one-year use limit for romosozumab, what should be the next step in long-term management?

Outcome and Future Directions

At 3 months post-transition, the patient:

- Showed continued improvement in spinal BMD

- Had no significant change in femoral BMD

- Was cleared for low-impact physical activities

Though it’s early to isolate romosozumab’s full effect, the sequential anabolic approach is proving beneficial.

Figure 2. Positive change was seen at AP-Spine and Femoral neck since initiation of anabolic therapy. Spine BMD improved by 13.5% since anabolic therapy, although prior teriparatide limits attribution to romosozumab alone.

Key Takeaways:

- Fragility fractures in young adults warrant aggressive investigation.

- Bone health assessment should include BMD and biochemical work-up.

- Treatment sequencing can maximize anabolic response and manage patient adherence.

- Maintenance therapy will play a critical role in long-term outcomes.

REFERENCES:

- Burge, R., et al. (2007). Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 22(3), 465–475.

- Nelson, B., et al. (2012). Osteoporosis in men: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 97(6), 1802-1822. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-2801

- Male osteoporosis. (n.d.). American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE). Retrieved from https://pro.aace.com/sites/default/files/2019-05/Male_Osteoporosis.pdf

- Mendoza, E. S., Lopez, A. A., Valdez, V. A. U., & Mercado-Asis, L. B. (2016). Osteoporosis and prevalent fractures among adult Filipino men screened for bone mineral density in a tertiary hospital. Endocrinology and Metabolism, 31(3), 433–438. https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2016.31.3.433

- Ferrari, S., et al. (2012). Osteoporosis in young adults: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Osteoporosis International, 23(11), 2735–2748. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2030-x

- Herath, M., Cohen, A., Ebeling, P. R., & Milat, F. (2022). Dilemmas in the management of osteoporosis in younger adults. JBMR Plus, 6(1), e10594. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm4.10594

- Björnsdottir, S., Clarke, B. L., Mannstadt, M., & Langdahl, B. L. (2022). Male osteoporosis: What are the causes, diagnostic challenges, and management? Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 36(3), 101766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2022.101766

- Costantini, A., Mäkitie, R. E., Hartmann, M. A., et al. (2022). Early-onset osteoporosis: Rare monogenic forms elucidate the complexity of disease pathogenesis beyond type I collagen. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 37(9), 1623-1641. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.4668

- Williams, P. (Ed.). (2016). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology (15th ed.). Elsevier.

- Xia, W., Xu, L., & Su, H. (2008). Vitamin D deficiency and osteoporosis. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases, 11(4), 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-185x.2008.00398.x

- Bandeira, L., & Lewiecki, E. M. (2022). Anabolic therapy for osteoporosis: Update on efficacy and safety. Archives of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 66(5), 707-716. https://doi.org/10.20945/2359-3997000000566

- Vilaca, T., Eastell, R., & Schini, M. (2022). Osteoporosis in men. Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 10(4), 273-283. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8595(21)00447-1

- Kobayakawa, T., Kanayama, Y., Hirano, Y., Yukishima, T., Nakamura, Y. (2024). Therapy with transitions from one bone-forming agent to another: A retrospective cohort study on teriparatide and romosozumab. JBMR Plus, 8(12), ziae131. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm4.10594

- Liu, L., Clifton-Bligh, R. J., Girgis, C. M., & Gild, M. L. (2024). Extending the therapeutic potential: Romosozumab in osteoporosis management. Journal of the Endocrine Society, 8(11), bvae160. https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvae160