Larizza Yrish Ramos-Mercado, MD, Jose Gabriel Go, MD, Kyle Patrick Eugenio, MD, Model Grace Montes-Buna, MD, Joshua Servande, MD, Sara Jane Labbay, MD, Jerome Dylan Montalbo, MD

Division of Endocrinology, University of the Philippines-Philippine General Hospital

As a tertiary government hospital, the Philippine General Hospital (PGH) receives referrals from across the country. With the volume and diversity of these cases, it is inevitable to encounter complex conditions involving multiple clinical questions where each answer, like a line of dominoes, often sets off another.

This is the case of a 33-year-old female who presented with aggressive behavior and signs of virilization that began in adolescence. She was reared as female and had no other significant medical history. Due to worsening behavior, she sought consult with a private physician, where hormonal evaluation revealed elevated testosterone levels. Additional laboratory tests showed polycythemia, hyponatremia, and hypokalemia. Abdominal CT scan demonstrated bilateral adrenal masses, each measuring more than 10 cm in greatest dimension. The initial impression was bilateral androgen-secreting tumors. The patient was referred to the urology service for planned surgical intervention and was subsequently referred to PGH.

Yet, the case carried more than what first met the eye. On further probing, additional details came to light that provided more clues, offering deeper insight into the patient’s condition.

Her journey began at birth, when she was born out of wedlock and left in the care of a Canadian missionary nun in the Philippines, who took very good care of her. At one month of age, her guardian brought her to a local hospital due to foul-smelling vaginal discharge. On physical examination, ambiguous genitalia were noted, and she was initially assigned male at that time. She was sent home on antibiotics, and surgery was advised, but they were eventually lost to follow-up. At two months old, she developed recurrent episodes of vomiting, failure to thrive, poor growth velocity, and was admitted for a severe infection associated with hypotension and tachycardia. She also presented with recurrent hyponatremia. Laboratory tests and karyotyping later confirmed that she was genetically female. Urinary 17-ketosteroids and plasma renin were elevated, while plasma cortisol was below the reference range (see Table 1). Given such findings, she was diagnosed to have Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH), salt wasting, likely secondary to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. She was started on steroid therapy, which led to marked improvement, with resolution of adrenal crises and improved growth velocity. Patient had unremarkable childhood thereafter.

Table 1. Laboratory assessment done at two months old.

| Chromosomal analysis | Urinary 17-ketosteroid | Plasma Cortisol | Plasma Renin |

| 46, XX female | 7.8 umol/day

(< 3.5 umol/day) elevated |

108.7 nmol/L (141-555 nmol/L)

decreased |

2.35 ng/mL/hr (0.65-1.36 ng/ml/hr)

elevated |

At nine years of age, the patient developed difficulty sleeping, which prompted a consult with a private physician. Prednisone was discontinued on the physician’s advice. No recurrence of adrenal crisis was noted thereafter, but the guardian observed the onset of virilization.

Upon consult at PGH, patient was noted to have male pattern baldness, hirsutism, and a palpable abdominal mass on physical examination. Hyperpigmented labial folds and clitoromegaly was seen in her genitourinary examination. Further examination revealed the following results as seen in Table 2.

Table 2. Laboratory assessment done after consult at PGH

| Hormonal Panel | Result

(normal values) |

| Total Testosterone | 960.95 ng/dL (13.84-53.35)

33.32 nmol/L (0.48-1.85) *range for sex not specified |

| FSH | 1.17 mIU/mL (3.03-8.08 mIU/mL) |

| LH | 0.15 IU/L (1.80-11.78) |

| Estradiol | 146 pmol/L (Follicular 77.09-921.42 pmol/L) |

| TSH | 1.15 UIU/mL (0.27-4.2) |

|

17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) |

44 nmol/L

(0.3-3.3 nmol/L) |

| ACTH | 669 pg/mL (7-41)

|

| 8am cortisol | 170 nmol/L

(160-620 nmol/L) |

| Aldosterone | 170 pg/ml (35-300 pg/mL)

|

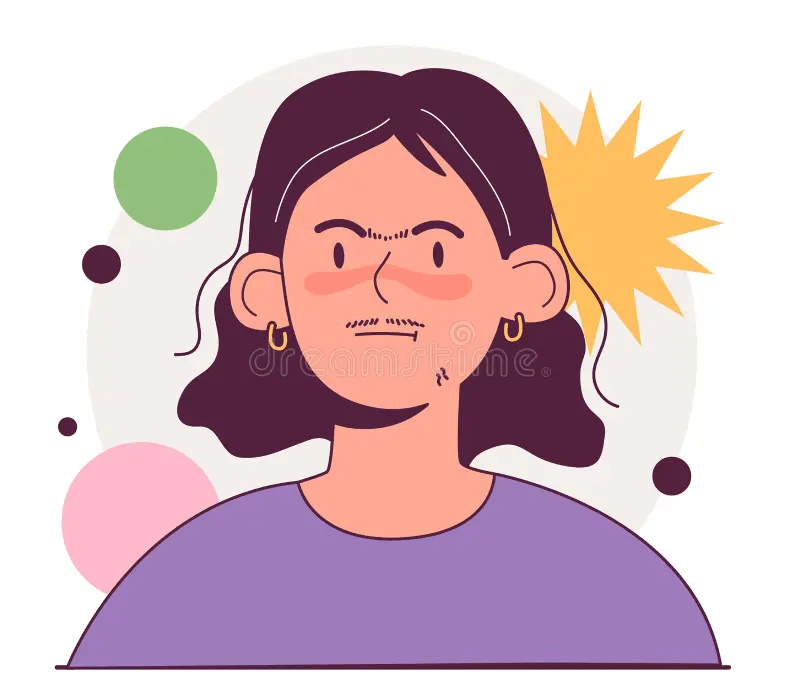

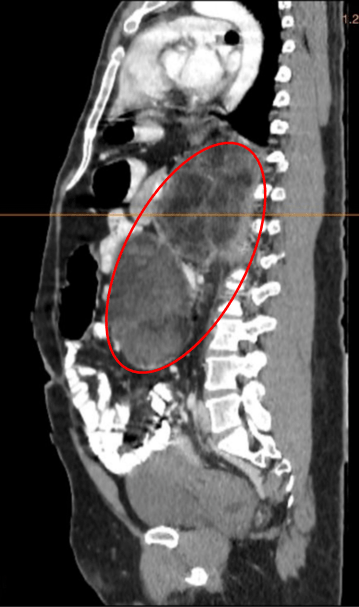

Adrenal CT scan showed heterogeneously enhancing masses with diffuse areas of fat densities and myeloid components seen in the bilateral adrenal glands measuring 21.9 x 12.4 x 12.3 cm (CCxWxAP) on the left and 11.1 x 7.2 x 6.9 cm (CCxWxAP) on the right with mean Hounsfield units (HU) -31 in the left and HU -18 in the right (see Figure 1).

A. |

B. |

Figure 1. A axial view, B. sagittal view. Abdominal CT images of the patient showing heterogeneously enhancing masses with diffuse areas of fat densities and myeloid components seen in the bilateral adrenal glands (red circle) measuring 21.9 x 12.4 x 12.3 cm (CCxWxAP) on the left and 11.1 x 7.2 x 6.9 cm on the right. HU values as follows: Left adrenal: Mean: -31 HU, Min: -114 HU, Max: 60 HU, Right adrenal: Mean: -18 HU, Min: -87 HU, Max: 41 HU.

Taken together, the history and examination of the patient gives us our first conundrum:

| In a patient presenting with signs of virilization and bilateral adrenal masses on imaging, what is our initial working impression? |

Given the absence of adrenal crisis despite discontinuation of prednisone, together with the presence of virilizing symptoms, the patient is most likely a case of classic simple virilizing Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia, probably secondary to 21-hydroxylase deficiency.

Is the abdominal CT scan findings expected in a patient with untreated CAH? This leads us to another conundrum:

| What are the differential diagnoses for an adult with CAH presenting with giant bilateral adrenal masses? |

The evaluation and management of bilateral adrenal masses generally follow the same protocol as unilateral cases. However, bilateral disease presents unique challenges, including the complexity of establishing differential diagnoses, determining the presence and laterality of hormone excess, confirming whether both masses share the same etiology, and considering possible familial syndromes. Data on adrenal masses in patients with CAH remain limited, mostly from case reports. A 2020 meta-analysis by Nermoen and Falhammar reported a 29.3% prevalence of adrenal tumors in CAH, most commonly adrenal myelolipoma, followed by adrenal adenoma. The imaging phenotype of the adrenal masses must also be considered in this patient. The presence of heterogeneous features, with adipose and hematopoietic elements along with low HU values, supports the diagnosis of bilateral giant adrenal myelolipomas (AML).

The goal of treatment in CAH is to correct cortisol deficiency while suppressing ACTH overproduction. The patient was therefore started on Prednisone 5 mg once daily. Repeat laboratory tests showed a decrease in ACTH to 37.65 pg/mL and 8 AM cortisol to 96.68 nmol/L; however, 17-hydroxyprogesterone increased to 54 nmol/L. Was this an expected treatment response? This brings us to our next conundrum:

| In patients with CAH treated with steroids, what are the expected biochemical and clinical outcomes that would indicate adequate response to treatment? |

To avoid overtreatment with glucocorticoids, the Endocrine Society guidelines for classic CAH recommend targeting 17-OHP and androstenedione levels within the upper limit of normal to mildly elevated ranges, adjusted for age and sex. However, no optimal biomarkers or target values have been firmly established, and glucocorticoid dosing should be guided primarily by clinical indicators. In adults with CAH, annual physical examinations are advised, including assessments of blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), and Cushingoid features, along with biochemical testing to evaluate the adequacy of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement. In this patient, prednisone was increased to 7.5 mg/day, with plans to monitor biochemical parameters.

In relation to adrenal myelolipoma, studies have shown that medication nonadherence in patients with CAH may lead to prolonged periods of ACTH overstimulation and subsequent development of adrenal myelolipomas. This appears to result from a complex interplay of factors, including hormonal dysregulation, receptor overexpression, and inflammatory cell migration. Unfortunately, there is still no clear evidence that optimal steroid replacement can halt the progression of AML size or that adequate control of CAH can prevent AML formation, given the possibility of sporadic tumorigenesis.

While surgical intervention was being planned, the patient was unfortunately lost to follow-up and later returned with complaints of abdominal discomfort, constipation, and decreased stool caliber requiring laxative use. A repeat abdominal CT scan revealed interval enlargement of the bilateral adrenal masses with compression of adjacent bowel segments. Surgical intervention was reconsidered; however, the presence of giant bilateral adrenal masses brings us to another conundrum:

| What would be the optimal surgical plan for this patient – unilateral vs bilateral adrenalectomy? |

A multidisciplinary conference was conducted taking into account the patient’s history of poor follow-up, the presence of unilateral bowel compression, and the risk of adrenal insufficiency following bilateral adrenalectomy. Expert input was also sought from Dr. Alice Levine, an endocrinologist at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York and a member of the Endocrine Society. She emphasized that bilateral giant adrenal masses are expected in untreated CAH and are usually benign. She further recommended removing the symptomatic left adrenal mass while monitoring the right mass under glucocorticoid therapy. In determining the optimal therapy for our patient, it is important to consider the potential outcomes.

Unilateral adrenalectomy preserves residual adrenal function, reducing the need for lifelong high-dose steroids and carrying lower morbidity and mortality; however, remission is less predictable, recurrence may occur, and some patients eventually require contralateral surgery. In contrast, bilateral adrenalectomy provides more reliable and durable hormonal control, often normalizing biochemical markers and resolving hyperandrogenism and virilization, but it is associated with higher perioperative risk, the need for lifelong glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement, and greater vulnerability to adrenal crisis, particularly with poor compliance. While both approaches can improve quality of life, unilateral surgery is safer but less definitive, whereas bilateral surgery is more effective but best reserved for severe disease given its lifelong metabolic and treatment-related complications. Adrenal crisis has been documented following bilateral adrenalectomy, but it has not been widely reported after unilateral adrenalectomy. Ultimately, the choice between unilateral versus bilateral adrenalectomy requires a multidisciplinary case discussion and should be personalized, factoring disease severity, hormone levels and patient’s ability to comply with lifelong replacement therapy.

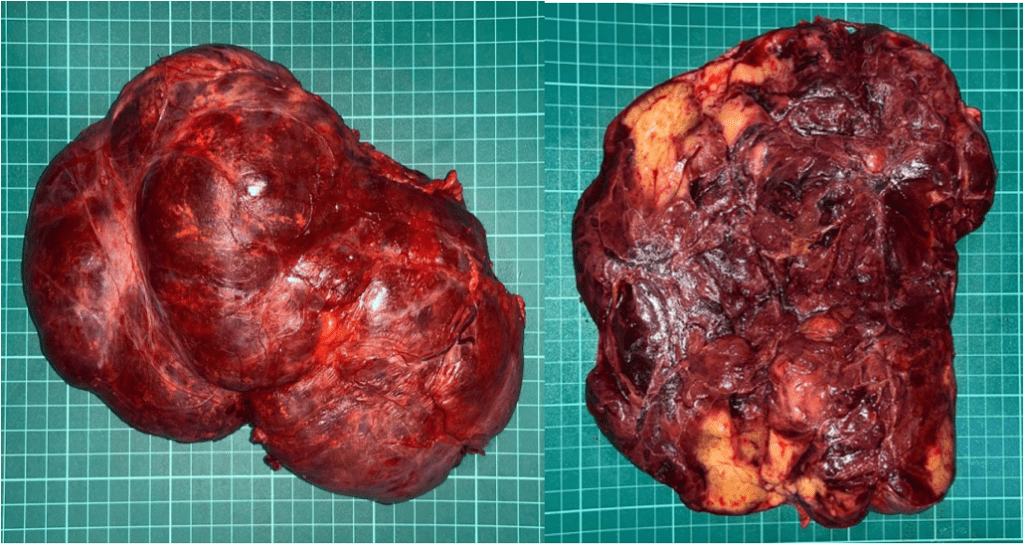

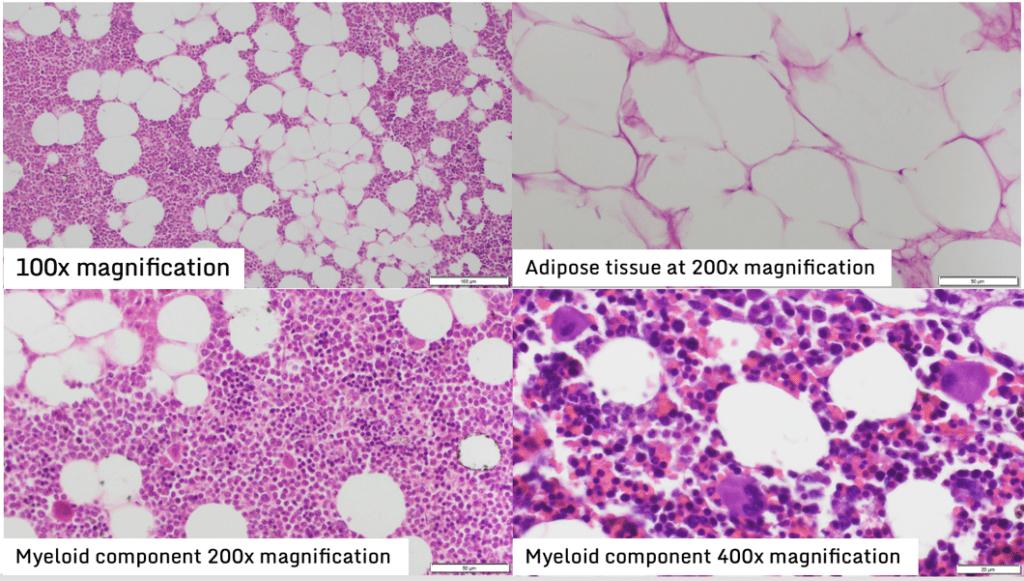

A left unilateral adrenalectomy was done to the patient. Preoperatively, patient was given IV hydrocortisone for stress dosing. Intraoperative and histopathologic findings are compatible with adrenal myelolipoma (Figure 2 and 3). Patient was discharged with unremarkable postoperative course with the final diagnosis of Giant Bilateral Adrenal Myelolipoma secondary to untreated Classic simple virilizing Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia likely secondary to 21-hydroxylase deficiency s/p left adrenalectomy.

Figure 2. Gross examination showed adrenal mass of 19.6 cm in greatest diameter consisting of a tan-grey irregularly shaped tissue, weighing 1.1 kilograms. Cut section showed heterogenous yellow to dark brown surfaces.

Figure 3. Histopathology showed myeloid components with myeloid and erythroid cells in various stages of maturation with increased numbers of megakaryocytes and the fatty tissues contain mature adipocytes with no atypical features.

On follow-up, the patient denied constipation or abdominal fullness. Testosterone level was within normal range at 3.16 nmol/L. Although subtle, improvement in her male-pattern baldness was noted, with her guardian observing small hairs growing on previously bald areas. Unfortunately, aggressive behavior persisted despite normalization of testosterone levels. The patient was referred to the Psychiatry service, where she was started on Olanzapine, with plans for a formal psychometric assessment.

Like a line of dominoes, the conundrums and decisions in this case were interconnected, each setting off new challenges. While we cannot control the first push, we can choose how to place each piece. Our collective response has shaped the patient’s course, always with the goal of achieving the best outcome. Through patience, diligence, and the guidance of our mentors, we were able to navigate the complexities and resolve the CAHnundrum with the following learning points:

- Adrenal myelolipomas can be seen in patients with poorly treated congenital adrenal hyperplasia; however, the exact mechanism of development of such tumors are yet to be understood but mainly attributed to chronic ACTH stimulation

- There is not enough evidence to prove that treatment with glucocorticoids can reduce tumor size of adrenal myelolipomas in adult patients with CAH

- Indications for surgery should be carefully evaluated and individualized, with giant myelolipomas causing pain and symptoms of mass effect, alongside risk of malignancy and significant tumor growth on serial imaging, being indications to perform surgical removal of the mass

- Unilateral adrenalectomy is considered in patients with bilateral tumors who have a larger and symptomatic tumor or with consideration of malignancy, in order to relieve symptoms while preserving adrenal function of the contralateral side

References:

- Santi, M., Graf, S., Zeino, M., Cools, M., Van De Vijver, K., Trippel, M., Aliu, N., & Flück, C. E. (2021). Approach to the Virilizing Girl at Puberty. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 106(5), 1530–1539. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa948

- Vassiliadi DA, Delivanis DA, Papalou O, Tsagarakis S. Approach to the patient with bilateral adrenal masses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;109(8):2136-2148. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgae164.

- Sweeney, A. T., Hamidi, O., Dogra, P., Athimulam, S., Correa, R., Blake, M. A., McKenzie, T., Vaidya, A., Pacak, K., Hamrahian, A. H., & Bancos, I. (2024). Clinical Review: The approach to the evaluation and management of bilateral adrenal masses. Endocrine Practice, 30(10), 987–1002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eprac.2024.06.015

- Nermoen I, Falhammar H. Prevalence and Characteristics of Adrenal Tumors and Myelolipomas in Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocr Pract. 2020 Nov;26(11):1351-1365. doi: 10.4158/EP-2020-0058. PMID: 33471666.

- Hamrahian, A. H., Ioachimescu, A. G., Remer, E. M., Motta-Ramirez, G., Bogabathina, H., Levin, H. S., Reddy, S., Gill, I. S., Siperstein, A., & Bravo, E. L. (2005). Clinical utility of noncontrast computed tomography attenuation value (hounsfield units) to differentiate adrenal adenomas/hyperplasias from nonadenomas: Cleveland Clinic experience. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 90(2), 871–877. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-1627

- Shenoy, V. G., Thota, A., Shankar, R., & Desai, M. G. (2015). Adrenal myelolipoma: Controversies in its management. Indian journal of urology : IJU : journal of the Urological Society of India, 31(2), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-1591.152807

- Murphy, A., Kearns, C., Sugi, M. D., & Sweet, D. E. (2021). Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Radiographics, 41(4), E105–E106. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2021210118

- Kaneto, H., Isobe, H., Sanada, J., Tatsumi, F., Kimura, T., Shimoda, M., Nakanishi, S., Kaku, K., & Mune, T. (2023). A Male Subject with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia due to 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency Which Was Diagnosed at 31 Years Old due to Infertility.

Diagnostics, 13(3), 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13030505 - Nicolaides NC, Willenberg HS, Bornstein SR, et al. Adrenal Cortex: Embryonic Development, Anatomy, Histology and Physiology. [Updated 2023 Jun 12]. In: Feingold KR, Ahmed SF, Anawalt B, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278945/

- Merke, D. P., & Auchus, R. J. (2020). Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Due to 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency. The New England journal of medicine, 383(13), 1248–1261. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1909786

- Bancos, I., Kim, H., Cheng, H. K., Rodriguez-Lee, M., Coope, H., Cicero, S., … Jeha, G. S. (2025). Glucocorticoid therapy in classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia: traditional and new treatment paradigms. Expert Review of Endocrinology & Metabolism, 20(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/17446651.2025.2450423

- Mallappa, A., & Merke, D. P. (2022). Management challenges and therapeutic advances in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Nature reviews. Endocrinology, 18(6), 337–352. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-022-00655-w

- Speiser PW, Arlt W, Auchus RJ, et al. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103 (11):4043–4088. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01865

- Calissendorff J, Juhlin CC, Sundin A, Bancos I, Falhammar H. Adrenal myelolipomas. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021 Nov;9(11):767-775. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00178-9. Epub 2021 Aug 24. PMID: 34450092; PMCID: PMC8851410.

- Kolli V, Frucci E, da Cunha IW, Iben JR, Kim SA, Mallappa A, Li T, Faucz FR, Kebebew E, Nilubol N, et al. Evidence of the Role of Inflammation and the Hormonal Environment in the Pathogenesis of Adrenal Myelolipomas in Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(5):2543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25052543

- Almeida, M.Q., Kaupert, L.C., Brito, L.P. et al. Increased expression of ACTH (MC2R) and androgen (AR) receptors in giant bilateral myelolipomas from patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. BMC Endocr Disord 14, 42 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6823-14-42

- Kethireddy M, Lee T, Rodrigues M, et al. (March 26, 2024) A Rare Case of Giant Bilateral Adrenal Myelolipomas in a Patient With Classical Congenital Hyperplasia. Cureus 16(3): e56953. doi:10.7759/cureus.56953

- Chen, S.Y., Justo, M.A.R., Ojukwu, K. et al. Giant Adrenal Myelolipoma and Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: a Case Report and Review of the Literature. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 5, 81 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-023-01398-z

- Hamidi O, Raman R, Lazik N, Iniguez-Ariza N, McKenzie TJ, Lyden ML, Thompson GB, Dy BM, Young WF Jr, Bancos I. Clinical course of adrenal myelolipoma: A long-term longitudinal follow-up study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2020 Jul;93(1):11-18. doi: 10.1111/cen.14188. Epub 2020 Apr 23. PMID: 32275787; PMCID: PMC7292791.

- Diana MacKay, Anna Nordenström, Henrik Falhammar, Bilateral Adrenalectomy in Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 103, Issue 5, May 2018, Pages 1767–1778, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-00217