Jessa Marie Chua, MD, Joannalyn Reyes, MD, Joseph Francis Sazon, MD, Dionise Ysabelle V. Bawal, MD, FPCP, FPCEDM

The mystery of endocrinology is that what you see is not necessarily what you will get. Like how masqueraders disguise themselves from others, so did our patient’s condition. Donning a mask of what seemed to be a common syndrome, underneath was something much more intricate.

This is a case of a 19-year-old female who sought consult due to excessive hair growth.

Infancy and childhood were unremarkable. Reproductive-wise, development was at par. The patient had thelarche at nine years old, pubarche at ten, and menarche at 11. Initially, she had regular menstrual cycles lasting 4 to 5 days at 30-day intervals. However, a year post-menarche (12 years old), she developed amenorrhea for 12 months. When menses resumed, she now had irregular menstrual cycles with intervals extending to 2 to 3 months by age 13.

Around this time, she also presented with weight loss and glucosuria. Consultation with a general practitioner led to a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus. No antibody testing was done. She was then started on insulin therapy.

At 14 years of age, two years post-menarche, there was recurrence of amenorrhea lasting 12 months. Coincidentally, she also noticed a sudden onset of rapid and excessive hair growth over the upper lip and temples, extending to the lower mid-jaw. She did not seek medical consultation, and no medications were taken during this period.

By age 15, the excessive hair growth progressed now extending to the chin. Although there was resumption of menses, they were still irregular occurring every 3 to 6 months. Upon consulting an obstetrician-gynecologist, a transrectal ultrasound revealed a normal uterus, multiple anechoic cysts in the right ovary (each <9 cm), and a unilocular right ovarian cystic mass (3.8 x 3.4 x 3.0 cm), which was considered to be a dermoid cyst. She was diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and prescribed oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) for six months, which resulted in regular menstrual periods occurring monthly. She was also noted to have elevated blood pressure at this time and was diagnosed with hypertension. She was started on amlodipine 10 mg once daily.

During follow-up with her OB-GYN, OCPs were extended for another six months. However, even with good compliance, she started to have oligomenorrhea, with menstrual cycles again occurring only every 3 to 6 months. Consequently, she discontinued OCPs and was lost to follow-up. During this period, she continued to experience persistent excessive hair growth, necessitating shaving every five days.

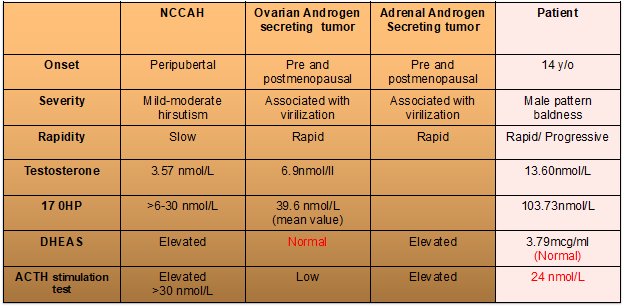

By age 18, the patient reported rapid hair loss in the frontal area of the scalp and a noticeable receding hairline. However, this was also accompanied by worsening excessive hair growth, requiring shaving every 2 to 3 days. Menstrual irregularities persisted, characterized by scanty bleeding. Due to the myriad of manifestations and apparent worsening of said symptoms, she consulted an endocrinologist. On physical examination, she has acanthosis nigricans but with no Cushingoid features. She was at Tanner Stage 5, without clitoromegaly. A modified Ferriman-Gallwey score of 23 was obtained. Due to male pattern baldness, which is a sign of virilization, an initial workup for hyperandrogenemia was done, revealing markedly elevated levels of testosterone at 13.61 nmol/L (NV: 0.48-1.85) and 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) at 34.28 g/ml. These initial laboratory results led us to three differential diagnoses: 1) Polycystic ovarian syndrome (probably a severe form), 2) Nonclassic Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia, 3) Androgen-secreting tumor (ovarian or adrenal origin).

However, as with most endocrinologic mysteries, there was still a lot of sleuthing and brainstorming we had to do. One may notice that the 17-OHP level was markedly elevated beyond the expected value for NCCAH and PCOS. Hence, DHEAS was requested, which turned out to be within the normal range. At this point, we were already leaning towards an ovarian tumor. But can a normal DHEAS level rule out an androgen-secreting adrenal tumor? Upon extensive research, we have found that not all androgen-secreting adrenal tumors exhibit the capacity for sulfation of DHEA, resulting in normal DHEAS levels on workup. Because of this unearthed fact on adrenal tumors, we decided to proceed with an ACTH stimulation test to strengthen our suspicion further. The use of ACTH stimulation test to determine an ovarian vs adrenal origin of androgen-secreting tumors has been presented in several case reports and case series. Our patient’s results were negative, as the 17-OHP level did not increase by more than two-fold rise or >30 nmol/L, highly consistent with an ovarian source.

Table 1. Summary table of patient’s laboratory results in comparison to expected findings in our differentials

If you may recall, our patient was noted to have an ovarian mass that was considered a dermoid cyst at the age of 15. She was already advised surgery at the time but she refused. Because of biochemical evidence strongly pointing to an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor, we decided to do a repeat transrectal ultrasound. Results revealed a 6-cm solid ovarian mass on the right and still with a polycystic ovary on the left.

Therefore, our final diagnosis for this patient is Hyperandrogenism secondary to an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor. She was referred back to OB-GYN for surgical removal of the ovarian tumor. The patient refused surgery at the time due to scheduling conflicts. However, she is scheduled to undergo surgery at the end of this month.

As endocrinologists, we cannot seem to sit idly by and wait for surgical intervention. The patient’s symptoms certainly posed detrimental effects on her quality of life and mild psychological implications such as low self-esteem. We started this patient on Finasteride to temporarily address the hyperandrogenic symptoms, which led to some improvement characterized by a slowing down of hair growth and resumption of regular menses.

Now that the masks have been removed and the true identity of the culprit has been revealed, let us end this masquerade ball with some clinical questions that we hope to find the answers to once our patient has undergone surgery.

- Although evidence of the effectiveness of Finasteride for androgen-secreting tumors is very limited, what mechanism could explain the patient’s improvement of symptoms?

- Was the development of PCOS secondary to the androgen-secreting ovarian tumor?

- Can androgen-secreting ovarian tumors present as cystic masses early on and transform into solid tumors with time?

- Is the androgen excess the culprit behind the patient’s early development of multiple comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension? If so, is there a possibility of diabetes and hypertension remission once the tumor has been removed?

References:

- Martin, K. A., Anderson, R. R., Chang, R. J., Ehrmann, D. A., Løbo, R. A., Murad, M. H., Pugeat, M., & Rosenfield, R. L. (2018). Evaluation and Treatment of Hirsutism in Premenopausal Women: An Endocrine Society* Clinical Practice Guideline. the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism/Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 103(4), 1233–1257. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-00241

- Escobar‐Morreale, H. F., Carmina, E., Dewailly, D., Gambineri, A., Keleştimur, F., Moghetti, P., Pugeat, M., Qiao, J., Wijeyaratne, C., Witchel, S. F., & Norman, R. J. (2011). Epidemiology, diagnosis and management of hirsutism: a consensus statement by the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society. Human Reproduction Update, 18(2), 146–170. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmr042

- Rosenfield R. L., Ehrmann D. A. The pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the hypothesis of pcos as functional ovarian hyperandrogenism revisited. Endocrine Reviews. 2016;37(5):467–520. doi: 10.1210/er.2015-1104.

- Rojewska, P., Meczekalski, B., Bala, G., Luisi, S., & Podfigurna, A. (2022). From diagnosis to treatment of androgen-secreting ovarian tumors: a practical approach. Gynecological Endocrinology, 38(7), 537–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2022.2083104

- Wong FCK, Chan AZ, Wong WS, Kwan AHW, Law TSM, Chung JPW, Kwok JSS, Chan AOK. Hyperandrogenism, Elevated 17-Hydroxyprogesterone and Its Urinary Metabolites in a Young Woman with Ovarian Steroid Cell Tumor, Not Otherwise Specified: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2019 Oct 27;2019:9237459. doi: 10.1155/2019/9237459. PMID: 31772787; PMCID: PMC6854983.

- The Pathogenesis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): The Hypothesis of PCOS as Functional Ovarian Hyperandrogenism Revisited. Endocrine re4views. 2016

- Yesiladali M, Yazici MGK, Attar E, Kelestimur F. Differentiating Polycystic Ovary Syndrome from Adrenal Disorders. Diagnostics. 2022; 12(9):2045. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12092045

- Derksen J, Nagesser SK, Meinders AE, Haak HR, van de Velde CJ. Identification of virilizing adrenal tumors in hirsute women. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:968–973

- Wong FCK, Chan AZ, Wong WS, Kwan AHW, Law TSM, Chung JPW, Kwok JSS, Chan AOK. Hyperandrogenism, Elevated 17-Hydroxyprogesterone and Its Urinary Metabolites in a Young Woman with Ovarian Steroid Cell Tumor, Not Otherwise Specified: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2019 Oct 27;2019:9237459. doi: 10.1155/2019/9237459. PMID: 31772787; PMCID: PMC6854983.

- Sheehan MT. Polycystic ovarian syndrome: diagnosis and management. Clin Med Res. 2004 Feb;2(1):13-27. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2.1.13. PMID: 15931331; PMCID: PMC1069067

- Evaluation and Treatment of Hirsutism in Premenopausal Women: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. 2018

- Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Due to Steroid 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.2018

- Miranda BH, Charlesworth MR, Tobin DJ, Sharpe DT, Randall VA. Androgens trigger different growth responses in genetically identical human hair follicles in organ culture that reflect their epigenetic diversity in life. FASEB J. 2018 Feb;32(2):795-806. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700260RR. Epub 2018 Jan 4. PMID: 29046359; PMCID: PMC5928870.

- Melmed, S., Koenig, R., Rosen, C., Auchus, R. J., & Goldfine, A. (2020, June 30). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology, 14 Edition: South Asia Edition, 2 Vol Set – E-Book. Elsevier India.

- Deplewski D, Rosenfield RL. Role of hormones in pilosebaceous unit development. Endocr Rev. 2000 Aug;21(4):363-92. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.4.0404. PMID: 10950157.

- Rosenfield RL, Deplewski D. The role of androgens in the development of biology of the pilosebaceous unit. Am J Med 1995; 98:80S